The sounds that we grew up with were things we took for granted. I always assumed that I would hear the five-days-weekly noon whistle at the B.F. Goodrich plant in Miami, Oklahoma. The sound that accompanied making a phone call would always be a spring-wound noise that accompanied the rotary dial. And purchasing something at most stores would involve hearing keys pushed and a ringing bell.

My first real job was sacking groceries at Phillip’s Food Center in Pea Ridge, Arkansas. I watched in amazement as the ladies would punch those keys at lightning speed, calling out each price so that the customer would hear them. And when it was all over, the drawer would open with that classic “ka-ching!”

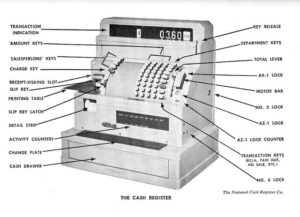

My grocery sacking job has, for the most part, disappeared, along with those manual registers. Nowadays, most checkers scan items over a laser, and also bag the customer’s groceries (unless the customer must do so himself). But today, the past comes alive once again for just a bit, as we experience the comforting mechanical sounds that accompany a 1960’s supermarket buy.

The cash register came into existence when saloon keeper James Ritty, of Dayton, Ohio, devised a contraption that would supplant the money drawer. It was very tempting for low-paid employees to pull a few bucks out for themselves, and Ritty’s cash register tallied actual sales totals. The money in the drawer had to match the machine’s calculations, or questions would be asked.

Former grocery store owner John Patterson saw tremendous potential with Ritty’s patented invention, and bought it outright. He worked feverishly to improve the design, and eventually employed a team of inventors. His business became the National Cash Register company, and soon dominated sales of the highly popular devices. By WWI, a million and a half cash registers had been sold in the US.

Patterson was a ruthless businessman who used legal shenanigans to stomp his competition. For instance, he patented the bell that would ring when the drawer was opened. He sued Heintz Cash Register Company because they sold a machine that made a cuckoo sound, and won! Heintz’s registers had to run silently. In 1912, NCR earned the wrath of the feds and was convicted of running a monopoly. I guess Bill Gates could have taught Patterson a thing or two about beating that particular rap.

Cash registers remained pretty much the same until the late 1970’s. One advance was the addition of a printed receipt for the customer. But by and large, cashiers punched up sales pretty much the way their parents and grandparents might have done it.

The advance in computers changed the way stores tallied sales. By the mid 80’s, cash registers had become networked devices, able to send their totals electronically to a central location, perhaps located thousands of miles away. The universal adoption of barcodes eventually caused the mechanical cash register to vanish altogether. Nowadays, even the smallest retail businesses use scanning and Point-of-Sale software to keep track of purchases.

Also vanished is the toy cash register that many of us grew up with. Durable models made by Structo and the like would often be handed down form elder to younger siblings, perhaps eventually making it all the way into a new generation.

All the modern-day toy registers I found for sale had two things in common: they were made of plastic, and they all had toy scanners attached. There were no friendly prices to pop up at the push of a key, no manual crank on the side to record the sale, and saddest of all, no cha-ching.

Fortunately for Boomers, Pink Floyd has immortalized the sound for all eternity.