In television’s early days, the various players among the networks weren’t clearly defined as to who would be successful and who wouldn’t. The giants, NBC and CBS, were pretty much assured of success, since they had access to hordes of familiar radio talents. Things weren’t so clear-cut for fledgling ABC, which had begun business in 1943. They didn’t have the dedicated listener base that the big boys had.

In television’s early days, the various players among the networks weren’t clearly defined as to who would be successful and who wouldn’t. The giants, NBC and CBS, were pretty much assured of success, since they had access to hordes of familiar radio talents. Things weren’t so clear-cut for fledgling ABC, which had begun business in 1943. They didn’t have the dedicated listener base that the big boys had.

Enter a fourth entity, one that I, and perhaps you, had never heard of before today: the DuMont Television Network.

DuMont Laboratories was founded in 1931 by Dr. Allen B. DuMont. He and his staff were responsible for lots of early technical innovations, including the first all-electronic consumer television set in 1938. The company’s television sets soon became the state of the art.

DuMont set up an experimental station in New York that year, and kept broadcasting throughout WWII, when CBS and NBC pulled the plugs on their similar installations.

The experimental station eventually became WABD, DuMont’s initials. He needed money, and cut a deal with Paramount Pictures for a 40% share of his network in exchange for $400,000. While it solved his cash flow problem, it ultimately doomed the little network that couldn’t.

When you’re small, and you don’t have radio talent to build on, you have to be innovative. DuMont Television certainly filled that bill. By 1949, they had three stations, in New York, Washington, D.C., and Pittsburgh. They set out to fill their programming time by ignoring the way the big boys were doing it.

For instance, DuMont had few programs like Texaco Star Theater or the Colgate Comedy Hour. Allen by and large refused to give sponsors such power, which they frequently used by insisting programming be tweaked to suit them. Instead, he sold commercial time to many different advertisers, to give his writers maximum creative control.

DuMont also didn’t deliver kinescopes to affiliates in different time zones, to be shown after the original east coast showing, or force them to have their own regional networks. Instead, he hooked up his later midwest affiliates via cable, so they were able to show programming live.

This technical innovation cost lots of money. So there wasn’t a whole lot left over for developing shows. But the little network accomplished an impressive collection of shows and talent nonetheless.

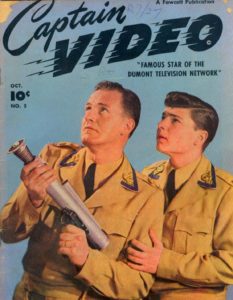

There was Mary Kay and Johnny, a comedy which was the first to dare to show a married couple in the same bed. Poor Lucy and Ricky were still in twin beds years later. And there was Gillette’s Cavalcade of Stars (one of DuMont’s few shows run by a single sponsor), which was hosted by newly discovered Jackie Gleason. And there was Captain Video, a wildly popular kids’ science fiction show that was short on set enhancements but long on encouraging kids to use their imaginations.

There was Mary Kay and Johnny, a comedy which was the first to dare to show a married couple in the same bed. Poor Lucy and Ricky were still in twin beds years later. And there was Gillette’s Cavalcade of Stars (one of DuMont’s few shows run by a single sponsor), which was hosted by newly discovered Jackie Gleason. And there was Captain Video, a wildly popular kids’ science fiction show that was short on set enhancements but long on encouraging kids to use their imaginations.

DuMont’s affiliation with Paramount stung them when they tried to get two more station licenses in Boston and Cleveland. A gotcha in FCC regulations nixed the deal, due to the fact that two Paramount stations existed. The FCC limited licenses at the time to five per network, and considered the Paramount stations (actually DuMont competitors) to be DuMont-owned as well.

Another coffin nail was a 1948 FCC freeze on licenses, due to a flood of applications. When they finally did allow new applications for stations in 1952, it was very difficult to obtain any VHF licenses. Thus, many new DuMont affiliates were forced to use the new UHF band, which would not become freely accessible until the mid 1960’s, due to the FCC not requiring televisions to have UHF tuners until then.

DuMont held on as long as they could, but finally went under on August 4, 1956.

So here’s to the little network that might have been as familiar to us as NBC, CBS, or ABC, but which was doomed by bad fortune, a bad business decision, and governmental red tape.