Recording tape is barely older than the senior members of the Boomer generation. It was introduced in the 1940’s as an alternative to direct-to-disc recording, which was how records were being produced prior to then.

The idea of putting music (or whatever) on a strip of magnetic tape was quite revolutionary. Recording studios embraced it at once. But tape for the home consumer was a different matter. It had some growing up to do before it would be widely embraced.

Tape came on big reels. It took a long time to rewind or fast-forward, as opposed to quickly moving a tonearm to different tracks on a record.

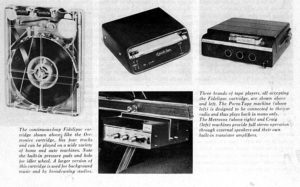

But the concept of recording tape for the consumer was too good to be ignored. As the 60’s debuted, several tape cartridge systems were under development, including a four-track, continuous-loop cartridge devised by the Lear Company, the Fidelipac system used by radio broadcasters, and the “Casino” cartridge introduced by the RCA company for use in its home audio units.

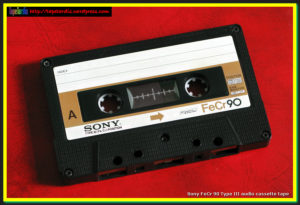

In 1962, Philips introduced a cartridge which held a tape 1/8″ wide, as opposed to the 1/4″ wide reel-to-reel tape that others were attempting to integrate int a self-contained cartridge.

The 1/8″ tape had crappy audio qualities when first introduced, and sales crawled. But Philips felt like they were on to something. They encouraged other companies to develop the cassette technology, but to observe the standards that they had laid down by licensing its use. The result was a swarm of development on the cassette.

By 1968, nearly a hundred different manufacturers had sold more than 2.4 million cassette players worldwide. The cassette business was worth about $150 million. Thanks to worldwide adherence to the standards established by the Philips company, the compact cassette was the most widely used format for tape recording by 1970.

But the sound still sucked. There was a lot of hiss on the slowly-moving narrow tape, and audiophiles either listened to records, or four- and eight-track tapes. Some of them purchased music on reels of tape. For cassettes to take over the world, their fidelity would have to be improved.

That year, top-end cassette machine manufacturer began selling units with Dolby noise reduction. The idea was that high-end sounds would be amplified during recording, then muffled a bit during playback. The tape’s hiss would fade into the background.

It worked fairly well, but not as expected, in many cases. The first automobile cassette players were notoriously weak on high end sounds, and playing the Dolby-encoded tape with the Dolby compensation shut off would make the highs blast forth. The tape hiss would disappear as the highway noise would mask it. But when you listened to cassettes with the engine off, it was obvious that there was a ton of background noise.

But cassettes gradually nudged eight-tracks aside, and by 1980, dominated the market.

Nowadays, I listen to high-fidelity mp3’s on a car stereo that reads memory cards. I put sixteen hours of music on a single gigabyte card. And it sounds perfect.

But I grew up with cassettes loaded with hiss that also played beautifully, as long as you were going at least fifty miles per hour.