The Beatles were at a critical point in the summer of 1966. An offhand quip by John to a reporter friend about how the Beatles were more popular than Jesus had drawn the ire of conservative self-titled Christians all over the world, but particularly in the US Bible Belt. Their protests often included public burnings of Beatle albums. Let’s face it, when angry people burn ANYTHING, it ain’t pretty. Plus, the rigors of the road had all of them thoroughly burned out on touring. So in August of the year, they all agreed live performances were no longer in their plans, and they sat down and got to work on their next album.

With Beatlemania’s flames no longer fanned by concerts, and with John’s remark carrying a bad taste in many people’s mouths, the group’s continued success depended heavily on their next album’s reception.

Their decision not to tour probably was very influential on their decision to create a massively produced album which could never be performed live. And this would reveal hidden talents the Fab Four had for making absolutely stunning music.

Their decision not to tour probably was very influential on their decision to create a massively produced album which could never be performed live. And this would reveal hidden talents the Fab Four had for making absolutely stunning music.

The group had become familiar with many instruments since the days when all was recorded on two guitars, bass, and drums. The new album would incorporate sitars, calliopes, Hammond organs, electric pianos, and orchestras of strings, brass, and woodwinds.

The album would also include massive overdubbing via the four-track recording system. And the themes of its music would extend far beyond teenaged love.

This trend actually began with 1965’s Rubber Soul, which stretched its wings a bit with Nowhere Man, In My Life, and Norwegian Wood, which was basically an account of an afternoon “quickie.” 1966’s Revolver likewise featured only three songs whose theme’s were simple romance, and also included Lennon’s LSD-influenced Tomorrow Never Knows, which invited us to “turn off your minds, relax, and float downstream.” Bloody hard to do while a herd of elephants is stampeding by in the background!

So the public had every reason to expect the Boys to spread their creative wings with their next release. And they didn’t disappoint.

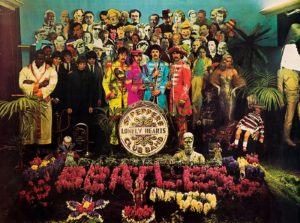

When fans finally saw the album in June, 1967, they were blown away by the cover. it featured dozens of characters from movies, yogis, writers, historical figures, and strangely morose looking Madame Tussuad’s figures of the Beatles themselves. Uh oh, that would contribute to future rumors that Paul was dead. By the way, here’s a nice site that will let you identify all of the subjects on the cover.

But the music inside would be even more stunning. The heavy production work at Abbey Road Studios was evident in the opening track, which featured a crowd in the background as well as a brass band. Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds wove a magical path around an imaginary world. Yes, its title just happened to start with L, S, and D, but the always bluntly honest Lennon maintained to his dying day that the song was based on a picture son Julian drew him and titled. I believe him.

But the music inside would be even more stunning. The heavy production work at Abbey Road Studios was evident in the opening track, which featured a crowd in the background as well as a brass band. Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds wove a magical path around an imaginary world. Yes, its title just happened to start with L, S, and D, but the always bluntly honest Lennon maintained to his dying day that the song was based on a picture son Julian drew him and titled. I believe him.

She’s Leaving Home was a maudlin tale of a daughter’s deciding to hit the road, leaving a note informing her parents of the fact. Its musical accompaniment was a simple harp and strings. That one hit home hard when my own son departed the household in the same manner.

George gave the world a good dose of Indian music with Within You, Without You. A droning tambura in the background, multiple sitars, and other exotic instruments played by Indian musicians accompanied George’s spacey vocals.

The album’s magnum opus was the coordinated medley of its last three songs. Good Morning, Good Morning was a slightly less cacophonous song than Tomorrow Never Knows, but was pretty noisy in its own right. Its lyrics referred to death, a US breakfast jingle, and a British sitcom (Meet the Wife), among other mundanities. It was accompanied by loud brass, guitars, livestock, dogs, birds, and a clucking chicken that wonderfully became the opening guitar lick for the next song.

The reprise of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band follows. It was allegedly recorded in one take, in stark contrast to the rest of the album. As it fades into the sunset, the first gentle guitar strums of A Day in the Life can be heard.

This amazing song, actually two songs in one, was a joint effort of Lennon and McCartney (actually one of a very few, despite all of their Beatle songs being credited to both of them). John wrote the surrealistic opening and closing, which referenced plans to fill potholes, a horrific car crash, and one of his own movies, How I Won the War, while Paul wrote the middle about being late for work and hopping on a double-decker bus and having a “smoke.”

Bringing the lyrics to life was a full orchestra which was stretched rubber band-taut by mixing-board-magic. The first time, it allowed for a segue into Paul’s section. The second, it climaxed the song, which ended on a doom-laden piano note that was held for almost a whole minute. As if that weren’t enough, there was also a few seconds of incomprehensible chatter on some versions, but not on my original US album.

The album lifted the Beatles to new heights of artistic popularity, and every album they would release afterwards saw them going massively different new directions, both as individuals and as a group.

Sgt. Pepper has grown in time, as all great works should, and sounds as fresh today as it did in 1967, IMHO. We were lucky, indeed, to have the Beatles to listen to as we grew up.