One of the great societal changes that took place during the 60’s was the banding together of the nation’s youth under a common shared cause.

One of the great societal changes that took place during the 60’s was the banding together of the nation’s youth under a common shared cause.

That cause was protesting the war in Vietnam. The war itself was a drawn-out affair that was mired in red tape and bureaucratic rules of engagement, and the only sure thing that was coming out of it was lots of young men in the primes of their lives being sent home in bodybags.

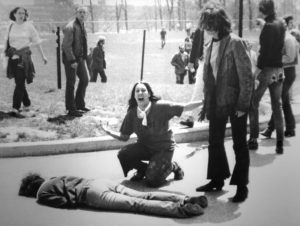

By the end of the decade, protesting had reached its acme, as students at universities all over the nation staged protests, some peaceful, some, like that at Kent State University in 1970, tragically violent.

Four students gave their lives on may 4, 1970. Another suffered permanent paralysis. But one can’t simply point a finger at the Ohio National Guard and cry villainy. There is more to the story than that.

Sometime around 1990, I read James Michener’s book Kent State: What happened and Why. It was a real eye-opener to me, and I recommend you search your own local library to see if a copy is available.

Michener painted a picture that is far from that described by those who would decry the incident as a case of trigger-happy Guardsmen who decided to take out students in an act of murder.

The protests at the university were caused by Nixon’s April 30th speech announcing his plans to accelerate the war by invading Cambodia. A noisy protest took place the next day on the campus’s commons area. Plans were made for a further demonstration on May 4.

That evening (May 1), large groups of students were gathering at downtown bars, still seething over the latest news from Washington. By now, according to Michener’s account, professional rabblerousers were strategically whipping the students into an uncontrolled frenzy.

A fire was lit in the middle of Kent’s Main Street, windows of businesses were broken, and the cops showed up to close down the bars.

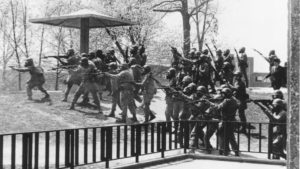

The next day, a Saturday, the mayor of Kent called in the Ohio National Guard to help maintain order. Students held another protest on the campus, and someone torched the ROTC building. Incidentally, the building itself had been boarded up and was soon to be demolished.

The next day, a Saturday, the mayor of Kent called in the Ohio National Guard to help maintain order. Students held another protest on the campus, and someone torched the ROTC building. Incidentally, the building itself had been boarded up and was soon to be demolished.

Again, Michener presented evidence that outside entities set the building on fire, making it appear that the students were behind it.

Then, there are the Guardsmen themselves. Some of them were, indeed, patriotic WWII vets who despised the fact that the students were defying Uncle Sam. But many of them were youngsters themselves, the same age range as the kids on campus, and many Guardsmen of all ages were sympathetic to the students’ cause. But the overwhelming emotion that the troops felt was fear. An unruly, angry mob is a frightening thing indeed, especially when driven by those whose business it is to stir up trouble.

On Monday, May 4, students gathered to attend the rally which the school itself had announced had been canceled. About 2,000 students gathered anyway, and attempts were made to break up the assembly. This climaxed with a thirteen-second volley of shots being fired, causing the four deaths and nine injuries.

Much investigation took place afterwards, with officials at the school being given the primary blame for what had happened. Two of the dead students had never participated in the protests, one of them being an ROTC member. The injured and dead were all a goodly distance away from the troops when shot.

All in all, it was a tragic, terrible mess. And, according to Michener’s book, the ones that were most responsible all got away scot-free. Hey, that theory holds a lot more water than the average Oliver Stone fantasy.