There are a few individuals out there who either inspire love or hatred. No in-between. I use the Dallas Cowboys as an example. Much of America loves the team, at least an equal amount despise them.

There are a few individuals out there who either inspire love or hatred. No in-between. I use the Dallas Cowboys as an example. Much of America loves the team, at least an equal amount despise them.

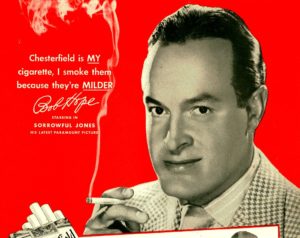

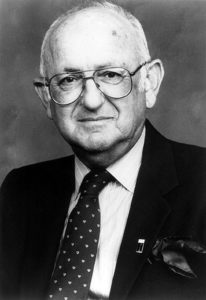

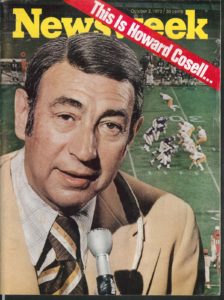

Howard Cosell was such a man. A poll in the 70’s revealed that he was both the most loved and most hated sports broadcaster out there. That summed him up nicely.

Born Howard William Cohen in Winston-Salem, NC, in 1918, he moved to Brooklyn as a child. His parents pressured him to become a lawyer, and he did just that, graduating from New York University School of Law and being admitted to the New York Bar in 1941.

However, instead of going to work as a lawyer, he joined the United States Army Transportation Corps and was quickly promoted to major.

When the war was over, he began practicing law in Manhattan. Many of his clients were professional and amateur athletes, and he found himself drawn to the whole athletic scene. In 1953, he was asked to host a show on ABC Radio involving Little League baseball stars. He did so, without pay, for three years. At that point, he decided to hang up his law diploma and pursue a full-time career as a broadcaster.

His first big gig was conducting pre- and post-game shows alongside Ralph Branca for the brand-new New York Mets. Showing the style that would be his trademark, he spared no mercy to the hapless team as they bungled their way through their first seasons.

About this time, he began hosting a syndicated radio show called Speaking of Sports. I heard it many times in my life. I know that WLS radio carried it, among many, many others. That show lasted until he chose to end it in 1992.

Cosell continued to be used by ABC, moving into television as the 60’s wore on. One of his most famous gigs was calling boxing matches. A rising star named Cassius Clay began to capture the country’s attention, and Cosell was heard to announce many of his fights.

Cosell continued to be used by ABC, moving into television as the 60’s wore on. One of his most famous gigs was calling boxing matches. A rising star named Cassius Clay began to capture the country’s attention, and Cosell was heard to announce many of his fights.

One such bout was the night Ali (then Clay) knocked out Sonny Liston with the “phantom punch.”

Then, in 1967, Ali announced his intention to go to prison rather than serve in the US Army. Much of the country castigated him, but Cosell defended his decision. He criticized the stripping of his title, drawing the anger of those who considered Ali a draft dodger.

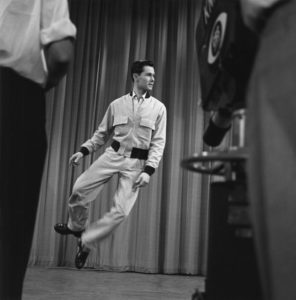

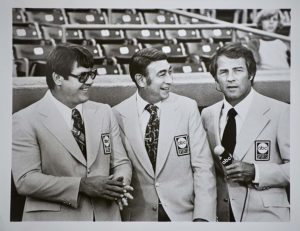

In 1970, Roone Arledge invited Cosell to be one of three announcers for ABC’s Monday Night Football. His acerbic observations were a perfect compliment to Don Meredith’s cutting up and Frank Gifford’s strictly business calling of play by play.

MNF became the most successful sports show in history. As Howard grew more confident in his role, his observations became more barbed. Much of the public began despising his “telling it like it is.” Bars began holding contests where the winners would get to heave bricks through TV screens when Howard began rolling.

Cosell continued to broadcast boxing matches, too. His call involving Joe Frazier getting decked by George Foreman is one of the most famous ever made.

Cosell continued to broadcast boxing matches, too. His call involving Joe Frazier getting decked by George Foreman is one of the most famous ever made.

But in 1982, while broadcasting a bloody bout between Larry Holmes and pathetically undermatched Randall “Tex” Cobb, he announced that he was through with the sport. The awful match came just two weeks after Duk Koo Kim had died in the ring at the hands of Ray Mancini. Cosell said during the broadcast “I wonder if that referee is [conducting] an advertisement for the abolition of the very sport that he is a part of?”

In September 1983, he drew the wrath of some hypersensitive morons when he used one of his pet phrases he had used for small, quick players, “little monkey,” to describe Alvin Garret (yes, he was black) during a particularly exciting run. Cosell, who was colorblind in the truest sense, suffered shame as a result of the public outcry.

Oh joy, the PC era had officially begun.

He quit MNF the next year, then penned a harshly critical book called I Never Played the Game in which he trashed practically everyone who had worked alongside him over the years while doing his Monday Night gig. ABC fired him shortly afterward.

I never like Cosell when I was a teenager. That’s because I didn’t understand him. He was never in awe of athletes. He would call a spade a spade (that’s not a racial statement, PC police) and would never hold back criticism that was earned. I feel he sadly let his bitterness get in the way of his objectivity when he wrote his book, but I miss him.

I wonder what he would have to say today about Barry Bonds and Roger Clemens.