If ever a TV show defined what was cool circa 1966, it was The Wild Wild West. from its unforgettable theme song to its intense animated opening (did he REALLY slug that woman??) to its futuristic gadgetry with a Victorian look (which I flashed back to the first time I saw The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen), The Wild Wild West had it all.

If ever a TV show defined what was cool circa 1966, it was The Wild Wild West. from its unforgettable theme song to its intense animated opening (did he REALLY slug that woman??) to its futuristic gadgetry with a Victorian look (which I flashed back to the first time I saw The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen), The Wild Wild West had it all.

It was also pretty darned violent for its time, hence my mother’s distress over the fact that I loved watching it.

But she didn’t deem it bad enough to forbid me, she would just make it clear that she didn’t approve.

But her tacit disapproval wasn’t enough to keep me from being tuned in on as many Friday nights as I could have control of the TV. The ones that I missed I eventually saw after school as it aired on the local station about 4:00 in the afternoon in the early 70’s.

The premise for The Wild Wild West was simple enough: James Bond-type gadgetry in 1870 or so. James West and Artemus Gordon were Secret Service agents in the hire of President Ulysses S Grant. Their job was to traverse the country in the world’s most luxurious train and take care of problems stirred up by various crazed geniuses, including the show’s repeating character, evil Dr. Miguelito Loveless.

The premise for The Wild Wild West was simple enough: James Bond-type gadgetry in 1870 or so. James West and Artemus Gordon were Secret Service agents in the hire of President Ulysses S Grant. Their job was to traverse the country in the world’s most luxurious train and take care of problems stirred up by various crazed geniuses, including the show’s repeating character, evil Dr. Miguelito Loveless.

The various mad inventors would come up with sundry doomsday devices that would be foiled by James West’s charm and bombs, guns and the like that were hidden in his clothing. Artemus Gordon would assist by becoming different personae, as he was a master of disguise.

Now what kid wouldn’t eat that up?

The show followed a cute trend that was shared by may others of the 60’s: consistent naming of the episodes. The Man From U.N.C.L.E. titled each episode “The (fill in the blank) Affair.” Rawhide used the “Incident (FITB)” format. For TWWW, it was “The Night of …”

TWWW and Star Trek seemed to have the occasional parallel plotlines. One I remember in particular was the concept of speeding up your metabolism so much that the world around you appeared to be standing still. I don’t know the episode names, but on TWWW, Jim dropped a glass that hung in mid-air to demonstrate the unique condition. On Star Trek, humans in the animated state sounded like buzzing insects to normal people. In both cases, the concept was amazing. I’m surprised it hasn’t been explored more in the world of entertainment.

The luxurious train that the duo traveled on deserves some mention. The train cars itself were a static stage set, of course, but the engine has been around. The locomotive, a 4-4-0 named the Inyo, was built in 1875 by the Baldwin. It did service for the Virginia and Truckee Railroad in Nevada. It was purchased by Paramount Pictures in the 1930’s. Besides being used for TWWW, it also appeared in tons of westerns, including Union Pacific, Red River, and John Wayne’s Mclintock!. It also showed up in some other classics like Meet Me in St. Louis. Nowadays, it’s owned by the state of Nevada, and it’s still running.

Unfortunately, The Wild Wild West has slipped off of television, as far as I know. Buts its original episodes are out on DVD. And of course the Will Smith/Kevin Kline 1999 movie is out there as well, a decent flick, IMHO. And the theme song will live on forever. In fact, I find it impossible to get it out of my head!

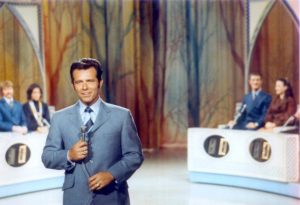

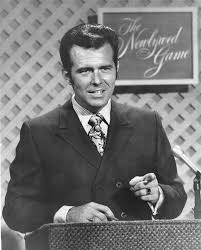

The Newlywed Game debuted in 1966, and ran on ABC until 1974. It was syndicated off and on from 1977 to 2000. Bob Eubanks hosted the show every year except 1984, when Dating Game host Jim Lange took over for a season.

The Newlywed Game debuted in 1966, and ran on ABC until 1974. It was syndicated off and on from 1977 to 2000. Bob Eubanks hosted the show every year except 1984, when Dating Game host Jim Lange took over for a season.