“I want my MTV” was the catchphrase of the early 80’s. But years earlier, producer Burt Sugarman saw a market for a rock and roll TV show that would take the medium just a bit farther than American Bandstand.

“I want my MTV” was the catchphrase of the early 80’s. But years earlier, producer Burt Sugarman saw a market for a rock and roll TV show that would take the medium just a bit farther than American Bandstand.

Late night TV was an untapped market in 1972. Once Carson was done, it was signoff time. So when Sugarman approached NBC execs with his idea of a Friday night show that would ride on Johnny’s coattails, and that would draw in the teenage demographic that was still wide awake at that hour, he was surprised and disappointed that they turned him down. Unfazed, he produced the first episode, bought the airtime (with help from Chevrolet), and televised it. The result? Great ratings, and reconsideration by the NBC execs.

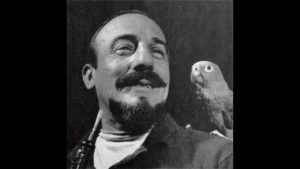

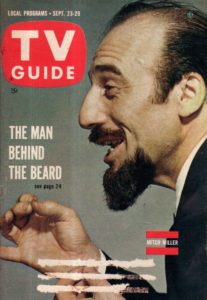

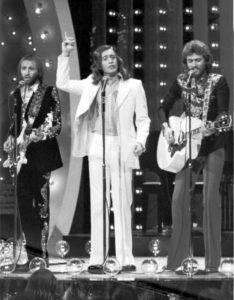

Sugarman grabbed up rising star deejay Wolfman Jack, who was being blasted across the US and Canada from a 250,000 watt Mexican radio station. A year later, he would appear in the smash hit American Graffiti. Good move, Burt.

The show would be hosted by a different musician each week (except for a year run with Helen Reddy as the regular lead), with the Wolfman providing his own running commentary. And man, did it attract the big names.

Groups and individuals who appeared on The Midnight Special during its eight-year-run included John Denver, Mama Cass, Harry Chapin, War, Linda Rondstadt, Ike and Tine Turner, The Doobie Brothers, Billy Preston, Loggins and Messina, blues legends Brownie McGhee and Sonny Terry, George Jones and Tammy Wynette, Aretha Franklin, Jerry Lee Lewis, aargh, I could fill up a web page with the names.

Comedians also stopped by. They included George Burns, Richard Pryor, George Carlin, Andy Kaufman, Bill Cosby, David Brenner, Martin Mull, and Robert Klein.

The show inspired an ABC copycat, In Concert. And it no doubt also put the idea of MTV into some creative exec’s head.

It was so much fun for thirteen-year-old me to stay up late Friday night, with my parents sound asleep, and jam to some great rock and roll. Ironically, now that I’m forty seven, my own son does the same thing while dad snores. Only he has access to the 24-hour-a-day version, while I had to wait until midnight (Central Time) to hear the Wolfman and listen to the best music that could be delivered through a three-inch television speaker.

We lost the Wolfman in 1995. Burt is still with us. He produced Children of a Lesser God and Crimes of the Heart in 1986, but has pretty much retired.

But we Boomers have fond memories of a show that the two talents joined up to give us some seriously great late-night rock and roll.