The word “hippy” used to conjure up some very strong emotions. WWII veterans would snort with disgust at the idea of a bunch of smelly, pot-smoking longhaired kids who dared to defy Uncle Sam by burning their draft cards. Why, such yellow cowards would have been tarred and feathered back in the day!

The word “hippy” used to conjure up some very strong emotions. WWII veterans would snort with disgust at the idea of a bunch of smelly, pot-smoking longhaired kids who dared to defy Uncle Sam by burning their draft cards. Why, such yellow cowards would have been tarred and feathered back in the day!

Youngsters had different point of view. Many admired people who would dare to live an unconventional lifestyle. And the idea of protesting a war that made less and less sense every day was easily related to. And long hair was decidedly cool. And you didn’t HAVE to smoke pot. Beer was easily obtainable in those days for Saturday night fun.

So many small towns sported their own versions of hippies. My parents were quite strict, so no long hair in the Enderland household. However, many kids’ parents were quite tolerant of their children’s appearance, as long as they stayed out of trouble. So Miami, Oklahoma had a few kids running around in tie-dyes, jeans, sandals, and sporting long, glorious hair.

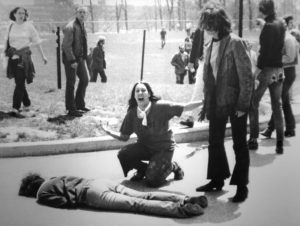

We didn’t have any organized Vietnam protests in our cozy town of 10,000. But there were plenty of peace signs on t-shirts. There was lots of graffiti like “Draft beer, not our boys” scrawled prominently in places like the nearby Baxter Springs drive-in theater (The back side, of course. It wouldn’t be very neighbortly to ruin the movie screen). So while we saw “unkempt” youth wandering the streets, we watched the classic hippies on TV or viewed them in Life Magazine.

But hippies were hated by many who were not young. They were viewed as a serious threat to the very fabric of society. And they felt slapped in the face by these young, mouthy protesters.

It’s not like their point of view didn’t have merit. Hippies weren’t known for tactfulness. It wasn’t unusual for outspoken hippies like Abbey Hoffman to deride anyone who didn’t agree with their views by trashing their opposers with obscene language and call them things like baby burners (or parents of baby burners, that hurt even more).

Of course, many hippies were simply kind, peaceful folk who didn’t like the turn society was taking. But they were lumped in with the loudmouths by the right-wing Hawks.

This led to bumper stickers like “You don’t like cops? The next time you need help, call a hippy!” But nobody was tarred and feathered, to my knowledge.

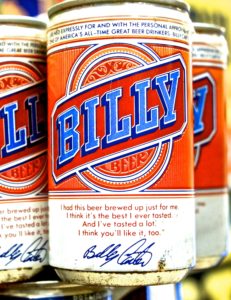

Hippies made their way into TV and the movies, besides the big weekly pictorial periodicals. Easy Rider featured the hippies on the commune out in the desert, cultivating the ground in vain, in Billy’s opinion. But Captain America assured him that things would work out well for the gentle rebels. Dragnet would frequently feature mouthy hippies being taught a tough lesson by Joe Friday. And Mod Squad attempted to meld youthful idealism with more traditional values with three cool cops (who also crossed paths with hippies from time to time, but attempted to relate a little more than Friday).

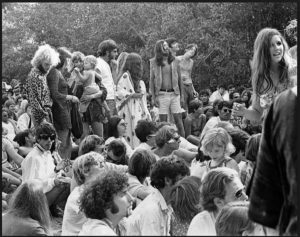

The Summer of Love in 1967 put hippies front and center. As they gathered at Haight-Ashbury at San Francisco, the rest of the world watched nervously. The previous year, opposition to the war was sparse. But in 1967, every peace sign was seen as a nose-thumbing (once considered an obscene gesture) at The Powers That Be. Suddenly, there was organized resistance to Vietnam, led by these long-haired freaks.

Well, society didn’t crumble. The war mercifully ran its course. We now do business with the same commies in Vietnam that many, many brave young men and women died to eradicate. Life is pretty weird.

Maybe the hippies who began living their lives in such an unconventional manner so long ago had a better grasp on reality than we thought.