The older members of the Boomer generation got to see lots of cool things. They watched Howdy Doody. They wore coonskin caps. They got to play with baking powder submarines.

The older members of the Boomer generation got to see lots of cool things. They watched Howdy Doody. They wore coonskin caps. They got to play with baking powder submarines.

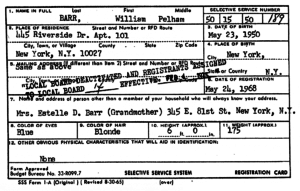

However, they also held a dread of one day turning eighteen. The draft was on, and a particularly nasty war was ongoing. Kids (and I mean that literally, as I was certainly a kid when I was eighteen) had to make profound decisions. Would they opt for ROTC? Would they volunteer for a more appealing form of service than the swamp-wading, booby-trap avoiding Army grunt? Or would they stay in school, or apply for CO status, or, head for Canada?

The draft began with a proclamation signed by Abraham Lincoln during the Civil War. Back then, a one-time payment would exempt you from having to serve.

After that, drafts would be implemented during times of war and suspended afterwards. In 1940, FDR signed the Selective Training and Service Act which created a draft during a time of peace, although the writing was clearly on the wall regarding the US’s future involvement in WWII.

After that, drafts would be implemented during times of war and suspended afterwards. In 1940, FDR signed the Selective Training and Service Act which created a draft during a time of peace, although the writing was clearly on the wall regarding the US’s future involvement in WWII.

But after the War, the draft stayed. Fewer young men were drafted in peacetime, but the possibility was there nonetheless. As wars like Korea and Vietnam escalated, more and more youths were sent the dreaded letter from Uncle Sam.

In 1969, a lottery was held which you did NOT want to win. Up until then, the government’s policy was to draft older individuals first as needed, meaning the odds would increase that you would be called up until you reached whatever cutoff year was in place. But the lottery chose birthdates at random as the primary prerequisite of when you would be selected. The later your birthdate was drawn, the less likely you would be called.

Twenty-year-olds were the primary target of the lotteried draft. If you turned twenty on September 14, 1969, you were virtually guaranteed being called up. That was the first date drawn. June 8 was drawn 366 (it was a leap year), so you had a pretty good chance of avoiding the dreaded letter if you were born on that day.

Twenty-year-olds were the primary target of the lotteried draft. If you turned twenty on September 14, 1969, you were virtually guaranteed being called up. That was the first date drawn. June 8 was drawn 366 (it was a leap year), so you had a pretty good chance of avoiding the dreaded letter if you were born on that day.

The draft started with twenty-year-olds, then progressed through each older year until 25. Then it dropped to nineteen, then eighteen.

However, even though both forms of the draft were set up to spare eighteen-year-olds, the fact is that many of them were still drafted. Curious.

As Vietnam slowed down, so did the draft. In 1973, it was discontinued altogether. I was fourteen. I was very, very happy. So was every other Boomer male who had evaded compulsory military service. In 1975, even registration was stopped.

But in 1980, Jimmie Carter reinstated registration due to the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. He intended to send a message to the Kremlin. Of course, now the Soviet Union is no more, and Russia is a democracy, and WE’VE invaded Afghanistan. Despite those strange twists of political intrigue, registration continues.

But today’s youths largely view it as a mere rite of passage. We who remember JFK, however, can recall a time when “draft” had a much more sinister connotation than a good cold beer or a chilly breeze in one’s house.