I was an avid Rolling Stone reader in the late 70’s. It was cool being nineteen years old and reading a hip publication that was considered to still be a bit “underground.” After all, its back pages featured ads for NORML! How cutting edge was that?

But I remember when I decided that the music magazine, which introduced me to artists like Neil Young and Bruce Springsteen, whom I still greatly enjoy, lost me as a regular reader.

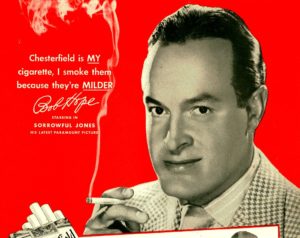

It was an issue that featured Bob Hope on the cover. The less-than-complimentary photo should have alerted me to the accompanying article’s venomous contents. Bob was skewered as a right-wing fanatical Hawk.

How much more pleasant a place the world would be if the subject of politics could be avoided at all costs.

We Boomer kids grew up with Bob Hope Specials on the TV at quite regular intervals. Bob was a radio star, and in the early 50’s faced the same decision as his contemporaries: what to do about TV?

Television was clearly the future of entertainment in those years. So the great radio stars began their migration to the idiot box. Many of them floundered, as the paradigms of being a star on TV differed from being a star on radio in subtle ways that baffled all involved. Jack Benny, Edgar Bergen, Fred Allen, and Ed Wynn opted for regular series with varying results. Benny’s show was a hit for a few years. The others couldn’t score like they did in the old days.

Hope looked things over and made a very astute decision: don’t be on every week. Instead, make each show a “special!” Have a dozen or so a year. That way, audiences wouldn’t grow tired of your routine.

That brilliant insight led to his being a regular prime time staple for nearly forty years.

Hope’s specials would typically involve an hour (or possibly ninety minutes) of singing, dancing, and comedy skits. The sponsor was Chrysler, and their familiar trademark at the opening would be burned indelibly into a kid’s mind. There was plenty of eye candy, too, as gorgeous babes of the era like Barbara Eden, Brooke Shields, Morgan Fairchild, Raquel Welch, Nancy Sinatra, etc., etc. would strut their stuff at the height of their popularity.

The shows would get great ratings for NBC, and the public would look for them in their regular irregularity.

Bob also had a long-standing tradition of entertaining US troops wherever they might be actively deployed. Evidently, this was the bee in Rolling Stone‘s bonnet. The Vietnam war was never more universally despised than the late 70’s, and anyone who hadn’t actively opposed it was viewed as suspect in character in a bizarre, miniaturized reversal of 1950’s Communist witch hunts.

John Wayne was the poster child for Hawks. His movie The Green Berets, in which a critical journalist Sees the Light about Vietnam, crossed the credibility line for many in the middle of the road, opinion-wise. They knew that Wayne’s red-white-and-blue stance was the diametrical opposite of the campus-trashing protesters, and common sense probably lay somewhere in between.

Hope, on the other hand, took gentle jabs at whomever was in office. His take on war? Its cause took a distant back seat to the need to provide its courageous participants with the distraction of entertainment.

So we were also treated to annual USO and Christmas specials during the Vietnam era. We knew that Les Brown and His Band of Renown were the swingingest musicians around. We knew that Thanks for the Memory was a great song without lyrics (at least I did, until I stumbled upon a late night weekend showing of The Big Broadcast of 1938). And we knew that Bob Hope would have his specials every couple of months until the end of time.

We were nearly right. Bob’s last hurrah was in 1996. Entitled Laughing with the Presidents, it costarred Tony Danza. You didn’t watch it? Unfortunately, neither did I. But it closed the book on a Boomer tradition that our parents also related to very well. IMHO, It’s a shame that my favorite Rock and Roll publication didn’t see it in the same light.