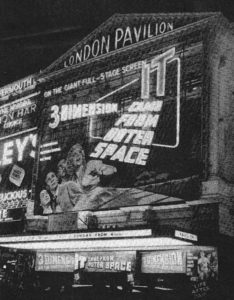

The neighborhood movie theater was a welcome spot for rainy and/or swelteringly hot summer afternoons in the 50’s. The drive-in theater was likewise a fond destination that many of us remember. One of the most amazing innovations that were enjoyed by the older members of the Boomer generation were 3D movies and comic books.

Man has always sought greater realism in the representations of the world which he has generated. It goes back to the day when a caveman would blow pigment over his hand placed on a rock wall in order to add a realistic, human touch to the mastodons and mammoths that he had drawn. By 1838, stereoscopic photography had been invented, bringing astonishing realism to tiny images viewed through a special device.

L’arrivée d’un train en gare de La Ciotat, filmed in 1895 by the Lumière brothers, is credited as being the first 3D film. Audiences would scream in terror as a speeding train appeared to head straight for them.

Except that the film wasn’t really 3D. it shocked the world with its realism, but it was just a simple two-dimensional film.

In 1915, three short films were shown in New York that were filmed using the anaglyphic process. Two camera lenses filmed two separate scenes from 2 1/2″ apart. When developed, the films were given treatment which overemphasized the colors so that viewing the finished film through red and green glasses would create a seamless three-dimensional image.

That same technology was called upon 37 years later by nervous Hollywood producers who saw the future of motion pictures seriously threatened by television. Thus, in 1952, Bwana Devil was released in 3D. The low-budget film created a sensation, and soon theaters all over the US were scrambling to add the ability to show three-dimensional films.

The next year, 27 more 3D films were released, including Vincent Price’s chilling House of Wax, considered one of Hollywood’s greatest horror films. 1954 saw the release of the 3D Creature from the Black Lagoon, another great scary flick.

The 3D movie craze came and went in a flurry. By 1955, only a solitary 3D movie was released. Thereafter, films would come out in 3D on an occasional basis. One of them was Ghosts of the Abyss, which my wife and I watched on a rainy Florida afternoon in 2003. I liked it, she didn’t.

Movies weren’t the only source of 1950’s 3D entertainment. Three Dimension Comics made its debut in 1953. The single issue, documenting the adventures of Mighty Mouse, sold over a million copies. Soon, 3D comic books were all over the newsstands, with the obligatory red/green glasses included as part of the package. Harvey, Archie, EC, DC, and practically all of the other major comic book publishers released three-dimensional versions of their familiar lines.

3D comics died out even sooner than films, the last one being published in 1954. Again, they have appeared off and on since then, but never in the 1950’s quantities.

Nowadays, we have, for the most part, given up on the idea of ubiquitous three-dimensional media. Instead, many of us have opted for HDTV’s. Perhaps not as exciting as seeing bright red blood fly three-dimensionally as many of us witnessed way back in 1953, but hey, it’s nice not messing with those darned glasses!

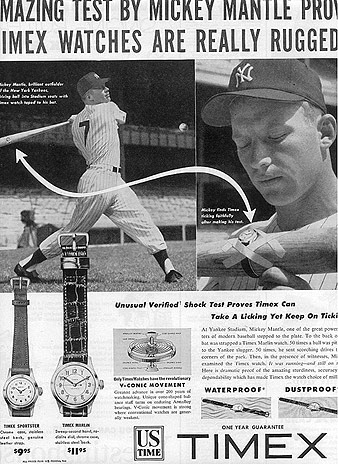

Print advertisements featured the new watch strapped to Mickey Mantle’s bat, frozen in an ice cube tray, spun for seven days in a vacuum cleaner, taped to a giant lobster’s claw, or wrapped around a turtle in a tank. Despite these and other extensive live torture tests, the Timex kept ticking. When John Cameron Swayze, the most authoritative newsman of his time, began extolling the Timex watch in live “torture test” commercials of the late 1950s, sales took off. Taped to the propeller of an outboard motor,tumbling over the Grand Coulee Dam, or held fist first by a diver leaping eighty-seven feet from the Acapulco cliffs, the plucky watch that “takes a licking and keeps on ticking®” quickly caught the American imagination. Viewers by the thousands wrote in with their suggestions for future torture tests, like the Air Force sergeant who offered to crash a plane while wearing a Timex. By the end of the 1950s, one out of every three watches bought in the U.S. was a Timex.

Print advertisements featured the new watch strapped to Mickey Mantle’s bat, frozen in an ice cube tray, spun for seven days in a vacuum cleaner, taped to a giant lobster’s claw, or wrapped around a turtle in a tank. Despite these and other extensive live torture tests, the Timex kept ticking. When John Cameron Swayze, the most authoritative newsman of his time, began extolling the Timex watch in live “torture test” commercials of the late 1950s, sales took off. Taped to the propeller of an outboard motor,tumbling over the Grand Coulee Dam, or held fist first by a diver leaping eighty-seven feet from the Acapulco cliffs, the plucky watch that “takes a licking and keeps on ticking®” quickly caught the American imagination. Viewers by the thousands wrote in with their suggestions for future torture tests, like the Air Force sergeant who offered to crash a plane while wearing a Timex. By the end of the 1950s, one out of every three watches bought in the U.S. was a Timex.