The world has reacted in various ways to the swine flu scare at presstime. Mexico has basically shut down, recent soccer games being played all over the country before empty stadiums. The fans aren’t allowed in, but the games get played anyway. Strange.

Anyhow, the CDC is calling for clear heads and calm. And you know what? The Boomer generation is doing exactly that. You see, we’ve been here and done this before.

On February 5, 1976, an Army recruit at Fort Dix told his drill instructor that he felt lousy, but not sick enough to see the medics or to skip an upcoming training hike. Within 24 hours, the soldier, 19-year-old Pvt. David Lewis, was dead. Doctors determined that he was killed by the same influenza which caused the pandemic (the world’s first) of 1918-19, which took a half-million US lives, and killed 20 million worldwide. Two weeks later, health officials disclosed to America that the disease, known as swine flu, had killed Lewis and hospitalized four of his fellow soldiers at Fort Dix.

What followed next was a panic of sorts. Word began spreading around that the 1918 pandemic was coming back.

The CDC ordered that vaccines be produced in numbers never before seen. And the general public was urged to get swine flu shots, as the depicted 1976 commercials demonstrate.

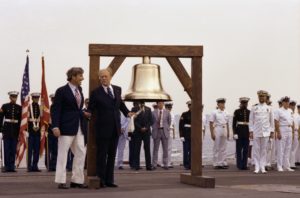

Even President Ford got his shot, and he invited camera crews into the Oval Office to film the event.

Even President Ford got his shot, and he invited camera crews into the Oval Office to film the event.

According to a doctor of that time, who was among many invited to Washington to meet with the CDC a few weeks after that first soldier’s death, the situation was destined to be a mess no matter who did what. The tone of the meetings was that 1918 must not be allowed to repeat. The CDC outlined an unprecedented program to manufacture and administer vaccines against the virulent strain. One of the concerns of the medical community was that all available resources would be diverted to the vaccination program, to the detriment of any other medical research.

But the decision was made, with President Ford’s firm backing, to proceed with the vaccination program.

The goal was to get everyone vaccinated before the fall/winter 1976 flu season. The government poured 135 million bucks into the project, a heck of a lot of 1976 dollars. And when October 1 arrived, the vaccinating began in earnest.

Two problems. Two BIG problems. One, the swine flu never showed up. Two, there were side effects from the vaccinations themselves.

The side effects were anticipated, and indeed, the number of them was, as expected, very small. However, the affected individuals received a lot of media coverage. One side effect was Guillain-Barre syndrome. This disease would cause the immune system to attack one’s own nerves, sometimes causing complete paralysis. Fortunately, complete recovery is common, if the person survives the initial onslaught. But many don’t, and actual deaths came to be attributed to the vaccine for the disease that never showed up.

The vaccinations stopped, after only 40 million inoculations. The goal was to vaccinate all 220 million Americans.

The effect was devastating on Ford’s administration, certainly contributing to his November loss to Jimmy Carter. But the effect was also devastating on immunology in general. The pharmaceutical industry had to absorb the cost of the unused 110 million doses of vaccine that had been produced at that point. The government refused to reimburse them. They were also being sued right and left by the families of the victims of side effects.

As a result, the drug companies began pulling out of the vaccine business. Even today, there are not as many vaccine makers as there were in 1976.

Thus ended the swine flu snafu, as it was commonly known in newspaper headlines. Unfortunately for us today, its effects have lasted well beyond that polyester year of 1976.