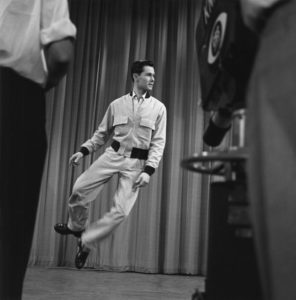

I Remember JFK did an article on Dragnet back in 2007, but it really didn’t pay enough homage to the man behind the show, Jack Webb. With that, today’s offering will attempt to give credit where credit is due, to the creative genius that accompanied one of the most familiar faces that we Boomers grew up with.

I Remember JFK did an article on Dragnet back in 2007, but it really didn’t pay enough homage to the man behind the show, Jack Webb. With that, today’s offering will attempt to give credit where credit is due, to the creative genius that accompanied one of the most familiar faces that we Boomers grew up with.

Jack Webb had an oft-imitated style of his own on the screen, one that made for great fodder for comedians, school playground thespians, and B-movie method actors. But perhaps his greatest talent lie in giving us some unforgettable television moments from shows that he created and/or produced.

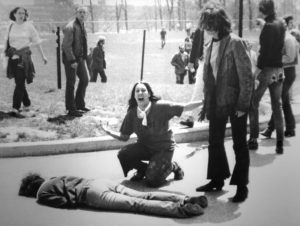

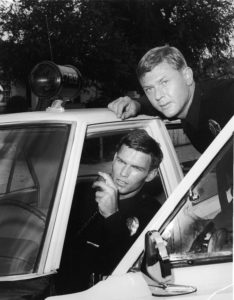

Webb’s first shot at creating a show without appearing onscreen was a home run to deep center. Adam-12 debuted in 1968, and enjoyed a seven-year run. The pilot revealed that officer Pete Malloy (Martin Milner, who had previously toured the country in a Vette in Route 66) was about to quit the force three weeks after losing his partner to a crook with a gun. Young, naive rookie Jim Reed was assigned to the depressed Malloy for a one-night deal, and by morning, the veteran decides to stick around and show the plebe how to survive. Thus began a show which would be a part of Boomer kids’ lives. It started out on a Saturday night, finished up on a Wednesday. But for the life of me, I can’t remember what night I watched it on growing up. Saturday, I believe. Any help from you readers?

Malloy was no-nonsense, by the book (except when he needed to not be by the book), and constantly reminded the greenhorn that it was life or death out there. In other words, he was Jack Webb. Jack Webb would thus “appear” in practically all of the shows that he would produce afterwards, you just had to look for him in a more sublime game of “Spot Hitch” (played every time a Hitchcock movie was on the screen).

The show strove for realism, right down to Shaaron Claridge. Hers was the voice that would come over the radio announcing “One adam twelve, one adam twelve, respond to a 211 in progress,” that of a real-life LAPD dispatcher. She even appeared personally in one episode, assisting Reed in running the plates of the next crook to be busted by the dynamic duo.

Malloy’s specialty was the Death Glare, given to Reed when the lighthearted newb would tread on sacred ground and offend the serious partner’s sensibilities. Example:

Malloy: You know what this is?

Reed: (smiling) Yes sir, it’s a police car.

Malloy: This black and white patrol car has an overhead valve V8 engine. It develops 325 horsepower at 4800 RPM’s. It accelerates from 0 to 60 in seven seconds; it has a top speed of 120 miles an hour. It’s equipped with a multi-channeled DFE radio and an electronic siren capable of admitting three variables: wail, yelp, and alert. It also serves as an outside radio speaker and public address system. The automobile has two shotgun racks – one attached to the bottom portion of the front seat, one in the vehicle trunk. Attached to the middle of the dash, illuminated by a single bulb, is a hot sheet desk, fastened to which you will always make sure is the latest one off the teletype before you ever roll.

Reed: Yes, sir.

Malloy: It’s your life insurance, and mine. You take care of it, and it’ll take care of you.

Reed: Yes, sir. You want me to drive?

Malloy: (Death Glare)

Oh yeah. Did I mention that Malloy did all of the driving?

Jack smacked another one to deep center with the January 1972 debut of Emergency! A mid-season replacement for Larry Hagman’s latest misfired shot at a post-Jeannie sitcom, the show soon caught fire among the viewers and took on a life of its own which would keep it on the air until 1978.

The show uniquely and separately told the story of the EMT’s and the ER staff. Gage (Randolph Mantooth) and DeSoto (Kevin Tighe) were the paramedics most frequently featured, with others making appearances as well, but these two have to be seen as the two main stars of the bunch who would go out into the trenches and extract victims.

Once they made their way back to the ER, the Webb clone made himself manifest. It was Kelly Brackett (Mark Fuller), the no-nonsense head ER doctor who didn’t have time for trivialities. He wasn’t above punching out unruly patients who might threaten his near-squeeze, nurse Dixie McCall (who, interestingly, had served in a Korean MASH unit before the CBS show made such a background famous).

The show was a favorite of mine, and lingered on as a series of TV movies after it ceased to be a weekly series in 1978.

Jack’s other creative efforts didn’t fare so well. They included O’Hara, US Treasury, Chase (Webb was the director for this one), The D.A., and Project UFO (it actually survived a second season). Jack’s company, Mark VII Productions, also was responsible for a few other series, including one success, Baa Baa Black Sheep (later retitled The Black Sheep Squadron).

One final note, Jack was the actor that was sought out by Animal House director John Landis to play the part of Dean Wormer. Jack turned him down.

He didn’t like the fact that the students were showing a lack of respect to authority.