We Boomers grew up with the greatest toys ever made. Indeed, the 1950’s-1970’s has been hailed as the Golden Age of toy manufacturing by more than one authority. And those toys were brought to us by a number of manufacturers who, sadly, have disappeared from sight.

We Boomers grew up with the greatest toys ever made. Indeed, the 1950’s-1970’s has been hailed as the Golden Age of toy manufacturing by more than one authority. And those toys were brought to us by a number of manufacturers who, sadly, have disappeared from sight.

I’ve already written about Kenner. Today, we cover three more beloved toy makers who have regrettably slipped below the waves of history and live on only in the memory banks of Boomer children.

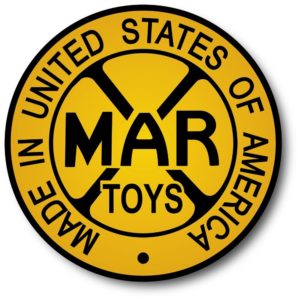

The first is Marx. “By Marx!” used to sign off all of their commercials, eagerly absorbed by many a 1960’s-era kid on a Saturday morning, the prime time for TV to show such ads in order to reach their maximum demographic. This Big Rail Work Train ad is one I remember well. It seemed that Marx’s specialty was BIG toys. That meant that it would take a special occasion to talk mom and dad into springing for one.

Marx was founded in 1919 in New York City by Louis Marx and his brother David. The brothers looked for innovative toy designs produced by others, bought the rights, and improved upon them. The strategy worked well. By 1922, both had become millionaires. Their business actually thrived during the Depression, and by 1955 Time magazine had declared Louis Marx the Toy King.

In 1972, the now 76-year-old Marx sold the company to Quaker Oats. In 1975, they in turn sold it to Dunbee-Combex-Marx, a British company. In 1978, that company went under, and so did the Marx name.

In 1972, the now 76-year-old Marx sold the company to Quaker Oats. In 1975, they in turn sold it to Dunbee-Combex-Marx, a British company. In 1978, that company went under, and so did the Marx name.

The Ideal Novelty and Toy Company was founded in New York in 1907 by Morris and Rose Michtom after they had hit it big creating the Teddy bear in 1903. The Teddy bear, of course, was invented to cash in on an incident in which Teddy Roosevelt refused to kill a bear which had been captured for that purpose.

In 1934, Ideal introduced Betsy Wetsy. Other triumphant Ideal toys included Battling Tops, Captain Action, Gaylord the Walking Bassett Hound, Ker-Plunk, the Magic Eight-Ball, Mouse Trap, Tip-It, and their final smash hit: Rubik’s Cube.

In 1982, with Rubik’s Cube riding high, Ideal sold out to the CBS Toy Company, which almost immediately itself disappeared. Thus was the inglorious end of the producer of some treasured Boomer toys. Many of its familiar creations continue to live on, though, particularly the one that started it all, the Teddy bear.

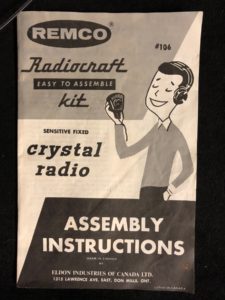

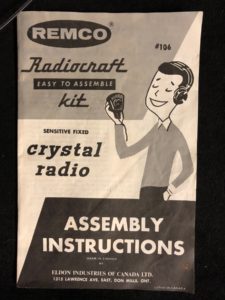

That brings us to our third vanished toy company: Remco.

That brings us to our third vanished toy company: Remco.

Remco was a relative latecomer in the Boomer toy manufacturing biz. They showed up sometime in the 40’s.

Among Remco’s contributions to our childhood memories were the official Beatles, Batman, Munsters, Lost in Space, and Monkees toys we played with. Remco managed to sew up the toy rights to these very lucrative franchises.

They also produced the famous Lyndon Johnson and Barry Goldwater play figures of 1964. What, you don’t remember them? That’s okay, neither does anyone else. 😉

Another obscure Remco toy that must have been absolutely amazing to see was their 1959 Movieland Drive-In Theater. According to Wikipedia,

(It) consisted of cars, a drive in board with car spaces, a place to list “Featured Movies” along with blue and white double-bill cards that slid into the marquee; the “movie” was a film strip that projected by a battery operated light bulb onto a 4″ x 6″ screen that attached to the drive in. Titles included Have Gun Will Travel, Mighty Mouse, (and) Farmer Al Falfa.

Can you imagine a 1959 kid setting up that puppy in his/her darkened bedroom? Wow!

Remco was acquired in 1974 by Azrak-Hamway International, Inc. The name held on until the apparent final product was released, 1994’s Swat Kats action figures. Never heard of Swat Kats? Maybe your kids did, they were aimed at their generation.

1994 is the last mention I could find of AHI/Remco, so I assume their demise must have occurred about that time.

Thus are the fates of three toy giants that fed our relentless appetite for playthings in the 50’s through the 70’s. They should stand as a stern reminder to big companies everywhere that no matter how well things are going for you now, you are only time away from becoming the subject of a nostalgia blog’s remembrance of something that disappeared when you weren’t looking.

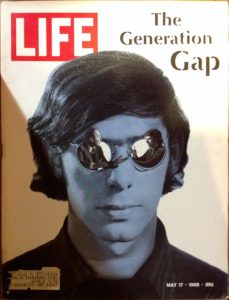

Perhaps it’s just me, but I recall being asked that question A LOT when I was a kid. Strangely, my own kids don’t remember being asked so much. But there was no doubt in my mind what I would be one day, far off into the future, when I stopped being a kid and transformed into a full-grown man: a SCIENTIST!

Perhaps it’s just me, but I recall being asked that question A LOT when I was a kid. Strangely, my own kids don’t remember being asked so much. But there was no doubt in my mind what I would be one day, far off into the future, when I stopped being a kid and transformed into a full-grown man: a SCIENTIST!