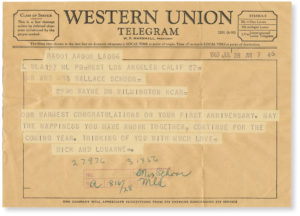

“Effective January 31, 2006, Western Union discontinued all Telegram and Commercial Messaging services. We regret any inconvenience this may cause you, and we thank you for your loyal patronage.”

Those words can be found at Western Union’s telegram section of their website. After being one of the most reliable communication means for well over a hundred years, its time has passed.

We Boomer kids have a few memories of telegrams, even though their decline was already quite evident when we were growing up. The telegram was viewed as a way to convey urgent news. And, as often as not, the ringing of the doorbell and the appearance of a Western Union employee with a telegram meant BAD news.

The telegraph was invented by Samuel F. B. Morse, as any kid who paid attention in school knows well. The Western Union company sprang into existence in 1851, using the exciting new technology to send messages all the way across the USA in less than a day. That was a quantum leap in an era when mail was the primary form of communication, and mailed letters would frequently disappear.

As steam trains sped along as fast as sixty miles per hour, communications needed to increase in speed as well. Telegraph wires crisscrossed the nation within a few short years, and soon, telegrams were sent out for things like birthday wishes, announcements of births or deaths, and, of course, bad news of emergencies.

The 1920’s and 30’s were when telegram usage hit its peak. Long distance calls were astronomically high in cost, and sending a telegram was the next best thing. Punctuation cost extra, so the familiar “stop” was thrown in to signify the end of a sentence. The four-letter word was no extra charge.

Our parents sent and received telegrams in WWII, as soldiers overseas were occasionally allowed to send them to their loved ones free of charge, and they would respond knowing that Western Union would reliably deliver their words back, regardless of where they were serving.

Telegrams were sent via a national system of printers called Telex. Teletype machines were tied together in their own network, and messages were printed on strips of paper that were cut and pasted onto the familiar yellow telegram.

I remember my parents getting a telegram or two back in the 60’s. Fortunately, neither one was to inform them of the deaths of any of their sons in the Vietnam war. Sadly, many parents were the anguished recipients of such carefully worded announcements that their sons would not be returning home alive.

So the knock on the door of a Western Union man carrying a yellow envelope is no longer something to be nervously answered. But that’s okay. We can get news even faster these days, be it bad or good.