One of the most sacred rituals that I recall from my childhood was that of getting into the car and driving, sometimes over an hour, to a favorite restaurant. The delicious saturated-fat laden food was a particular delight to my parents, who could remember the very lean times of the Great Depression.

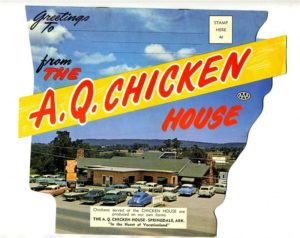

So perhaps once a month, we would pile into the Plymouth and head for locations like Chicken Annie’s, or Wilder’s, or the AQ Chicken House.

All three of these fine eateries are still around, I’m happy to say. Perhaps they have altered their menus to provide more health-conscious options, perhaps not. But they are still plugging away, providing unique cuisine that flies in the face of the plethora of generic chains that have become a part of our lives. And Boomers, that should make you smile. After all, if I can quickly come up with three examples of local eateries that have survived since the 60’s, I’ll bet you can too.

Now I’m not saying that there’s anything wrong with chains like Applebee’s, Red Lobster, Olive Garden, or Shogun. Indeed, there is much to love about the sameness and predictability of the franchise restaurant, especially when you are on the road and hungry.

But the unique eating places of our youth were very much savored by our parents, who faithfully returned again and again, sometimes driving an hour or more to get there. After all, they found out by trial and error that they were worth visiting. Perhaps the grapevine at work or at the beauty shop revealed that there was a place in Springdale, Arkansas, accessible only by narrow, curvy Arkansas roads, that served the best fried chicken this side of Alabama.

At any rate, our parents loved their favorite restaurants. And we kids loved it when they would take us along. This was a special treat for me, because it was much more common for them to leave me home on Saturday nights in the care of my older brother while they headed off to Joplin, thirty miles away, to feast at Wilder’s.

I also recall nice-looking eating spots that my parents avoided like the plague. Why was that? Was the food questionable? Was the staff less than pleasant? Was the atmosphere wrong?

I doubt that the latter was the case, because many of the often-visited places featured undecorated white walls, or ugly faded art prints of cowboy scenes, or water-stained ceilings. Clearly, chic ambiance was NOT the thing that drew my parents back again and again..

I recall pulling into the AQ Chicken House driveway about 1967 and seeing a dilapidated-looking building, with old barn wood everywhere. But there was also hardly a place to park. My parents would feast on the chicken, but my favorite was the batter-dipped french fries. Oh, the decadent delight!

Chicken Annie’s was another humble-looking spot, a half-hour drive from home. Sitting out in the middle of nowhere, it too drew a crowd of commuters who couldn’t care less about atmosphere, and who found its food too good to resist.

Wilder’s in Joplin was founded in the year that the stock market crashed, and has managed to survive lots of economic ups and downs since then. Sadly, such was not the case with Mickey Mantle’s Steakhouse (although the late Mick still has his name on a trendy New York eatery) and Rafters, which featured a huge fire-breathing dragon sign. I was completely spellbound as that neon-lit beast would spew out flames from its mouth every minute or so, illuminating the black Joplin Saturday night and burning itself indelibly into the memory banks of a rapt seven-year-old.

How about you? What favorite eating spots of your childhood are still around? Here’s hoping you can still visit your own personal equivalent of Chicken Annie’s, Wilder’s, or the AQ Chicken House.