When we were kids, our options at the local neighborhood grocery or the dime store were manifold. Most of the time, we walked out with candy. But sometimes, we would invest our hard-earned (or begged) coins on magical little flying machines made of balsa wood.

They came in little clear plastic packages with cardboard at the top. The hole in the cardboard allowed them to be hung on a rack, frequently at the top of the candy display, as I recall. The plain ones cost a dime, the fancier rubber-band driven models were 29 cents, as best I can remember.

Since I usually was given two nickels a day, buying a glider meant making a tough decision. I had to forego my morning candy fix and come back later in the afternoon in order to have ten cents to purchase my flying machine.

But as much as I loved the elegant little airplanes, I made the tough call many times, and walked home proudly carrying my plastic-wrapped wooden prize.

My craft of choice was usually the simple ten cent glider, for obvious reasons of affordability. However, sometimes I would manage to cajole mom into springing for a rubber-band powered model at the dime store.

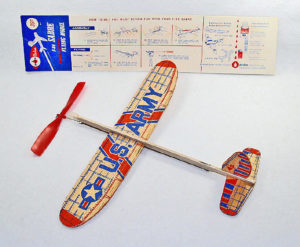

The propeller-driven plane was seriously cool indeed. The fuselage was a simple square stick that held a hook on the rear and a slide-on red plastic propeller holder on the front. It had its own hook, and the special long thin rubber band stretched the entire length of the stick.

The plane also had wheels. I guess a more skilled pilot could make it take off or land that way, but not me.

Powering the plane involved patiently turning the propeller backwards. The rubber band would become evenly twisted, then would take on a new shape as the twists would be transformed into large knots. When the entire rubber band was a series of large knots, it was time for the flight to begin.

Letting the plane go on its own on concrete would generally result in it running rapidly along the ground and eventually smashing into something. So I would launch the plane by throwing it skyward, just like it was an unpowered glider.

Eventually, the rubber band would break. That was not the end of the fun, though!

You could open the window on the car and hold the rubber-band-less plane into a thirty MPH breeze and the propeller would spin rapidly, as your imagination filled in the rest of the WWII battle scene taking place outside the Plymouth’s window. At some point, the wings might rip off in the stiff breeze. By then, however, I had gleaned many hours out of a 29 cent investment (that would be thirty cents including tax).

The simple glider featured instructions that allowed you to move the wings forward and back in the slot cut into the fuselage. This would cause the plane to do loops or streak straightly. You could also bend the horizontal stabilizer in order to cause it to turn to the right or to the left.

Eventually, the piece of metal at the front would dislodge, and we would learn how important it was for an airplane to be properly weighted in order to function. I remember it was a real eye-opening experience for me to learn that a plane could actually be too light to fly!

Another lesson that the cheap gliders taught us was that wonderful things came in small, inexpensive packages.

You can still find balsa wood gliders at the toy sections of many stores. The dime stores and the corner groceries are long gone, though. So is the ten-cent price. But you know what? It’s nice living in a rapidly-moving modern world with the added luxury of having memory banks full of wonderful moments from our childhoods.

The ones North Pacific made with the plastic tee that held the wings to the fuselage were my favorite, the additional dihedral gave the plane additional stability, allowed the wings to be adjusted for level flight or loops and stalls, plus they were swept back for higher speeds (a terribly important consideration at the time), and you could take the metal weight off the nose and slide the wings way back – so cool.