My older brothers grew up with the presence of a horrible, random terror that caused near-hysteria. It could strike absolutely anyone, but seemed particularly fond of children. Perfectly healthy, active kids could be transformed in a matter of days into paralyzed individuals who might require confinement in an “iron lung” just to take their next breath.

The scourge was poliomyelitis, commonly known as polio.

A series of outbreaks took place in 1921. Among those infected was a young adult named Franklin Delano Roosevelt. His strong legs were turned into paralyzed vestiges of what they once were.

Roosevelt was determined to press on despite his malady, and tried to always arrange to be photographed away from his ever-nearby wheelchair. But the American public knew that the man who would come to be their most beloved President was a victim of polio, and FDR spearheaded a drive to find a cure, or at least a prevention, for the disease.

In the early 20th century, the polio virus was transferred mainly by poor hygiene among babies and children. 90% of those exposed would develop antibodies and a lifelong immunity. However, the remaining 10% would be affected by symptoms ranging from minor affecting of muscle movement to complete paralysis.

In the early 20th century, the polio virus was transferred mainly by poor hygiene among babies and children. 90% of those exposed would develop antibodies and a lifelong immunity. However, the remaining 10% would be affected by symptoms ranging from minor affecting of muscle movement to complete paralysis.

As personal hygiene improved, exposure to the virus became less commonplace among children. But this worked two ways. The virus still survived, and would eventually come into contact with individuals who might have developed the needed antibodies at a very young age, but now had to cope with an unencumbered virus at a later age. I am good friends with a man who developed polio in the early 50’s at the age of fourteen.

Among the pioneers who fought polio were Sister Kinney, an Australian nurse who used physical therapy rather than immobilization to restore much muscle movement among the disease’s victims. The medical community resisted this outspoken Aussie’s techniques, but eventually she had persuaded many to come to the institute she founded in Minnesota. Among the patients who received care and regained muscle tone was Alan Alda.

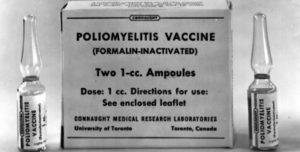

At the prevention end, a vaccine was being feverishly sought. In the late 1940’s, Albert Sabin was working on an oral vaccine. Jonas Salk was concentrating on an injected model. They both received government grants for their work, as did other polio researchers.

In the meantime, numbers of cases of polio began to surge. The average had remained at 20,000 new cases per year throughout the 40’s, but in 1952, the most-ever cases were reported in the USA: 58,000.

That year, Salk began testing a vaccine prototype at Watson Home for Crippled Children and the Polk State School, a Pennsylvania facility for the mentally retarded. The results were encouraging. By 1954, the vaccine’s test group included thousands of school children. The vaccine was effective, but not perfect. It provided immunity in 60-70% of individuals against against PV1 (poliovirus type 1), and over 90% of the subjects against the other forms of the disease.

In 1955, immunizations began to be given to the general population. The March of Dimes assisted in promoting and organizing vaccinations, and by 1957, the number of new US cases was down to 5600.

Meanwhile, Sabin and his team continued to work on their oral virus, and in 1958, it was tested and found effective. In fact, the immunity it provided lasted longer than that provided by the Salk vaccine. It replaced Salk injections in 1962 in American schools and hospitals.

By 1964, when I was five years old, a mere 121 cases of polio were reported in this country.

We Boomer kids grew up with lots of worries. But those of us who were among the last of the post WWII-population explosion were very fortunate that polio was something we talked about in the past tense, thanks to an army of researchers who had long before declared war on the crippling disease.