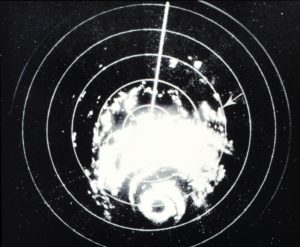

As regular visitors to this site already know, I grew up in Miami, Oklahoma, not in the heart of tornado alley, but certainly within spleen distance ;-). I remember being terrified with break-ins on TV shows from the likes of KOAM and KODE with reports of tornadoes in the area, complete with scary, indecipherable radar screens that showed ominous big white images against a black background.

What I was looking at was state-of-the-art of its time. Our parents grew up with absolutely no way to know bad weather was on the way except to look for signs like all of the cattle gathered up in one area facing the same direction. Perhaps they would look for a red sky at morning. Radio stations would help, but weather forecasting was still more art than science.

In 1957, a quantum leap was taken in the forecasting and tracking of bad weather. The first WSR-57 was commissioned at the Miami Hurricane Forecast Center. WSR stood for weather surveillance radar, and 57 stood for 1957, duh!

The radar unit was basically a WWII vintage piece of equipment, domesticized to look for cloud masses instead of enemy bombers. While a large advance in the science of meteorology, it didn’t show windspeed. It also only showed the thickest cloud masses, making subtleties like rotation difficult or impossible to discern. The parts were 40’s vintage, and repairs often consisted of scrounging through old boxes of stuff to find the right tube.

The WSR-57 radar units began spreading across the United States. One went up in downtown Kansas City in 1959. Key West, Wichita, Cincinnati, Galveston, and St. Louis all received units in 1960. The next year, Amarillo, Detroit, and Fort Worth got theirs. Weather hotspots were beginning to receive an additional tool to forecast bad conditions, and the hope was that local residents would be given opportunity to prepare for any onslaughts.

The WSR-57’s served our country well. Many of them were still functioning as good as new thirty or more years after deployment. The last of them was taken offline on December 2, 1996, at Charleston, SC, after an amazing 37-year run. Not bad for something that was essentially pieced together from parts that were manufactured to see action in WWII.

What ultimately replaced the original radar units was a new technology called 88-D. This stands for Doppler 1988. That was the year that the smart technology of measuring approaching and receding wind speeds to determine rotation was launched.

Of course, there were many other hi-tech features of Doppler radar. For one, computers were extensively used in the background, making for better alerting, compiling of data over time, and preservation of historical records.

The WSR-57 would flash blips on the screen, which would disappear with each rotation of the antenna. Operators made grease pencil markings on the screen to track the movements of cloud masses. Doppler would actually display a map, showing precise locations of cloud formations, which did NOT disappear with each pass.

Radar usage involves varying power output, adjusting antenna rotation speed, and also antenna pitch. It wasn’t unusual in the early days for operators to make these tweaks via cranks that turned huge rheostats. It took good physical stamina to be a meteorologist back then.

It also took serious training to make sense of the high-contrast white blips on the black screen. Thus, a kid already deathly afraid or tornadoes was further terrified by the ominous images that would be flashed up on TV by local weathermen Earl Ludlum or Lee George during the interminable breaks in network programming while we were experiencing bad weather.

But it was certainly an advancement, one our Depression-raised parents appreciated. My father had no problems understanding the weatherman and the radar display, thus, he never ordered us to take cover during the years that I have memories of Miami, Oklahoma, from 1963 to 1968. We had tornadoes hit close, I remember one tearing up some trees north of town, but our little tract home remained safe.

Nowadays, a colorful live radar display is depicted in the lower right corner of our high-def television, and the fine detail lets us see exactly where the squall line is while we’re enjoying a rerun of Andy Griffith on a weekday evening.

But those of us old enough to remember JFK can also recall when radar weather tracking was very much an art, subject to the interpretation of an educated user.